Barn to Lab: UGA Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

An old cattle barn finds new life as a lab facility

The University of Georgia spent about a year transforming a 71-year-old reinforced concrete and steel beam cattle barn into a classroom and laboratory building. The Ocean Sciences Instructional Center was officially dedicated in a ceremony held on Oct. 22 at UGA’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, a multidisciplinary research and training institution situated on Skidaway Island, which is near Savannah.

The architect for the Ocean Sciences Instructional Center was Cogdell/Mendrala of Savannah, GA, and the construction manager was New South Construction of Atlanta.

“It was an open-air cattle barn built in the mid-1940s by the Roebling family. They were northern industrialists that built that Brooklyn Bridge,” said Dr. Clark Alexander, director and professor, Skidaway Institute of Oceanography. Alexander notes that Robert Roebling, great-grandson of engineer John A. Roebling, one of the first developers of twisted wire cable, moved his family from New Jersey to Georgia in the 1930s. Robert and Dorothy Roebling established a breeding ranch for Hampshire hogs and Aberdeen Angus cattle, and even held their daughter Ellin’s wedding reception in the barn (with champagne on ice in the feed troughs), but they eventually they gave their property to the state of Georgia to establish a marine research center. The Skidaway Institute of Oceanography was founded in 1968.

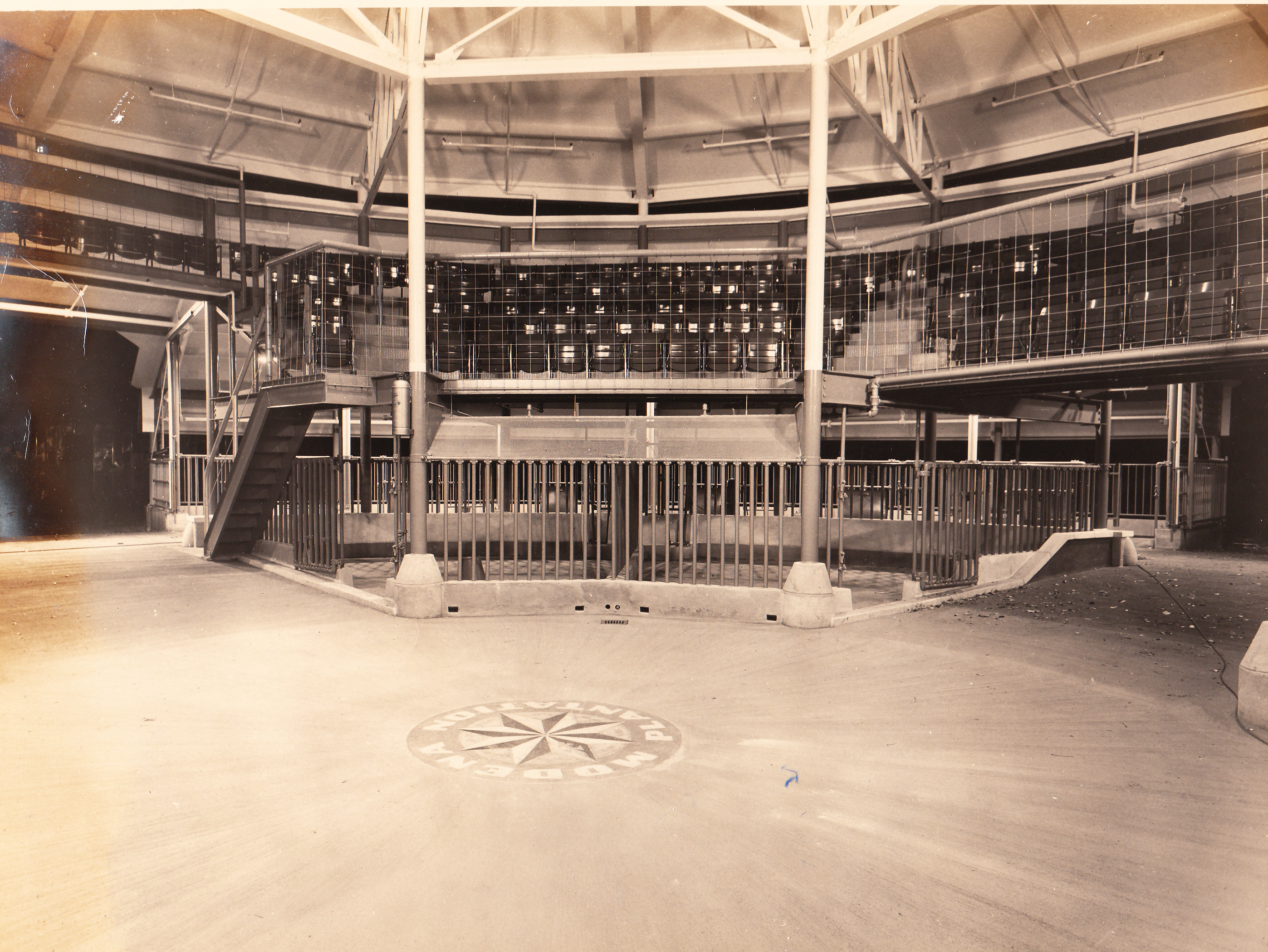

The present-day Ocean Sciences Instructional Center, during its time as a cattle barn.CREDIT: Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

The present-day Ocean Sciences Instructional Center, during its time as a cattle barn.CREDIT: Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

The idea behind the marine research center may have come from the Roeblings’ love of the sea—they spent much of their time on their three-masted schooner, the Black Douglas, before donating it to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1941, after which it served as a World War II patrol vessel and then went on to the Scripps Institute of Oceanography and Southwest Fisheries in San Diego. It also participating in the opening ceremonies of the yachting events portion of the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Currently known as the Aquarius, the rebuilt yacht is now privately owned.

The Skidaway Institute of Oceanography merged with the University of Georgia in 2013. UGA was eager to acquire the nearly 50-year-old establishment in its effort to consolidate local research institutions and make its universities more responsive to student needs. “Skidaway had expertise and an international reputation—a merger for the two of us seemed like a no-brainer,” says Alexander, adding that the institute’s association with UGA has given its recruiting pipeline a massive boost so that it can attract top talent.

Preserving the past

Although its official name is the Ocean Sciences Instructional Center, Alexander says that the facility is colloquially known as The Barn, as a nod to its bovine origins. The building was called the Modena Plantation when the Roeblings used it as a cattle facility. The recent renovation, Alexander says, made a “conscious design move” to preserve the building’s history while still modernizing it for present-day oceanography researchers. “There was no way we wanted to cover everything up … and, frankly, we didn’t have the budget to cover everything up or renovate the whole space into useful space,” he says. “So what we decided to do was embrace the industrial aesthetic, and highlight the architectural features.”

The Barn is round, says Alexander, noting that the shape presented a challenge for the design team: “Think about the issues surrounding trying to build classrooms and offices and labs within a circular structure where there are no right angles,” he says. “We put up cinder block walls around it to make it an enclosed space. Then it was used for staging oceanographic equipment, long-term storage of large bulky equipment that goes out to sea, and labs for tinkering with new equipment and instruments.”

“The whole barn was made out of large steel beams and a concrete roof on multiple levels. All of those features were preserved,” continues Alexander. “Half of the walls we put up initially were taken down. In the stalls around the perimeter of the building, we created two large distance learning classrooms to enhance our educational activities. Then we put in a large teaching lab, which will be used for hands-on education of students within the marine sciences.”

The newly renovated Ocean Sciences Instructional Center. The historic compass rose mosaic is visible under glass in the center of the floor.CREDIT: Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

The newly renovated Ocean Sciences Instructional Center. The historic compass rose mosaic is visible under glass in the center of the floor.CREDIT: Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

One of the most striking design features of The Barn is a compass rose mosaic, measuring about three feet across, situated in the middle of the floor directly under the skylight. Robert Roebling, when designing the original barn facility, calculated the exact latitude and longitude of the spot, the elevation above mean sea level, and incorporated a metal “needle” pointing to true North in the compass rose’s design. “Because we needed to bring the floor in the middle of the barn up by about eight inches, there was a problem about how to maintain the medallion in the middle of the building as a centerpiece,” says Alexander. He notes that no contractor wanted to cut it out and lift it out, for fear of damaging it. “So we ended up putting it under glass and raising the floor around it. That’s kind of a neat feature—[there is] LED lighting around edge of perimeter of the medallion so you can see it.”

“It really is like the 'heart' of the building, if you will,” he remarks thoughtfully.

Moo-ving from cattle to research

The Barn is home to a 144 sq. ft. prep lab, and a main teaching lab measuring 851 sq. ft. The prep lab features a hood, sink, a cabinet for chemicals, a refrigerator/freezer for chemicals and samples, an eyewash station, and an emergency shower. The teaching lab, named for the late UGA alumnus Albert Dewitt Smith Jr., has an 80-inch monitor wired into the network of the building so users can plug into network ports anywhere within the lab. Videos coming out of microscopes or camera are able to be shown to large groups. The Barn utilizes LED lighting with occupancy sensors, as well as sound, infrared, and motion sensors to determine if someone is in the room.

A unique feature of The Barn, Alexander says, is that the renovations included a “science on display” design, so that the public can view the marine science as it’s happening. One of the teaching labs features a three-panel glass wall so outsiders can observe what’s going on in the lab.

Another design feature is that the facility doubles as both a research building and a social gathering space. “In half of the inner ring of the building, we preserved all the beams and the concrete roof is all visible. We kept the beams exposed in about half of the building so that there’s an open space that can be useful for events or public lectures, and public outreach,” Alenander says.

The other half of The Barn was transformed into study rooms, and a reading room with a small library. Collaborative spaces enable small study groups to gather for homework, or faculty to meet and work on proposals. “When you need to work, you need to be in a place where you can control your environment,” Alexander says.

The future

Exterior view of UGA's Ocean Sciences Instructional Center.CREDIT: Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

Exterior view of UGA's Ocean Sciences Instructional Center.CREDIT: Ocean Sciences Instructional Center

Renovations are not yet complete at the Ocean Sciences Instructional Center. “Some of the things we wanted to do did not get done,” says Alexander, adding, “Within the budgetary constraints we had, I think we were always able to come to common ground after we discussed it enough.”

The Barn has two floors, and the original intention was for the upper floor (once used as a space for hay storage and cattle auction seating) to serve as an open collaborative space for scientists and graduate students to work together on proposals and manuscripts, behind storefront glass. However, the project saved $250,000 by nixing that feature for the time being, and instead sealing off the second floor behind drywall. The planning team built a stairwell that essentially leads to nowhere—at least, for now. “We are prepared when and if we find the money to move forward with the next phase of the project. I made sure that we installed the major infrastructure that had to be there to support those spaces, like the stairway,” says Alexander, noting that it is very expensive to retrofit and set footings for a stairwell. The second floor also needs adjustments to its air conditioning, electrical, and fire safety systems before it can be used by research staff and students.

“If you think about this project, it wasn’t new construction, it was a historic renovation, so that presented its own challenges because the person from the university who was the architect over the project was a preservationist,” says Alexander. “[There were] strong feelings about what should be preserved and what should be let go—appropriately so.”

Alexander says that those who once occupied The Barn, both during its time as a cattle facility and then as a research space, seem pleased with the recent renovations. He notes that original faculty members from the institute’s founding in 1968 have visited the new labs for tours. “At the dedication [ceremony]... there were a number of descendants of the couple that built the barn. They were all really excited at what had become of it for the next phase of its life,” he says.