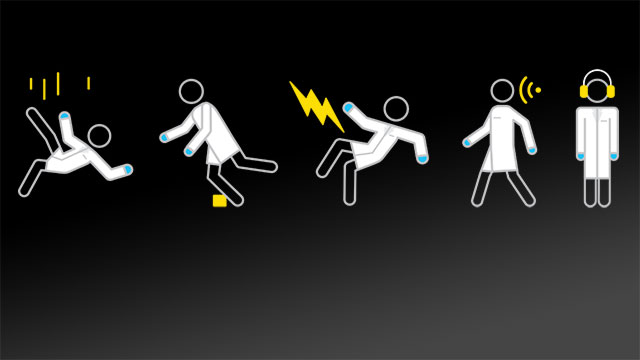

Falls, Electrical Shocks, and High Decibel Levels, Oh My!

The Safety Guys want to alert you to potential physical hazards typical of many research, academic, and production laboratories

Many laboratories present safety challenges. This month the Safety Guys want to alert you to potential physical hazards typical of many research, academic, and production laboratories. What do we mean when we say “physical hazards”? We mean conditions and situations that might lead to slips, trips, and falls, in addition to not so obvious hazards, such as electrical safety issues and high noise areas.

Most common first

First, perform a general facility inspection concentrating on walking/working surfaces, lighting, and egress pathways. It is imperative that emergency exit routes remain clear and unobstructed at all times. Make sure floors are smooth and free of cracks or lips that could catch or trip.

Slips, trips, and falls rank number one for accidents and injuries and are easily avoided. Most injuries are minor and arise from poor housekeeping. Organize storage areas to avoid creating hazards. Minimize chaotic accumulation of materials in storage areas that could cause tripping, hinder access, or present a fire risk.

A couple of tips for doing so include stacking and interlocking bags, containers, and boxes that are stored in tiers, and limiting the height so that they are stable and secure against tipping, sliding, or collapsing. Inspect storage racks, hand trucks, and other equipment to ensure good mechanical condition. Be sure to check the casters for any damage.

Another issue concerns proper lighting. Conduct an illumination survey, and measure those areas with low light. Compare results with recommendations by IES and ANSI.1 Ensure all lights within seven feet of the floor are protected against accidental breakage. Use plastic protective tubes over fluorescent bulbs prior to mounting, or install screens onto the fixtures. Finally, note areas with special lighting requirements and train employees to allow for eye adjustment before working in those areas.

Prevent electrical shock

While performing your facility inspection, look for electrical hazards. Improper use of extension cords or cords with cut, torn, or frayed insulation; exposed wiring; missing grounding plugs; open electrical panels; and overloaded circuits are ones we see frequently. Specialized equipment such as electrophoresis setups, biosafety cabinets, and wet-vacuum systems present less obvious hazards. Pay very close attention to wet areas. Equip all electrical power outlets in wet locations with ground fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) to prevent accidental electrocutions. Wet locations include outlets within six feet of a sink, faucet, or other water source and those located outdoors or in areas that get washed down routinely. GFCIs are designed to “trip” and break the circuit when a small amount of current begins flowing to the ground. Specific GFCI outlets can be used individually or installed in the electrical panel to protect entire circuits.

Related Article: The Best Accident Response Plan for Your Lab

Improper use of flexible extension cords is one of the most common electrical hazards. Extension cords must never substitute for permanent wiring. Check the insulation and make sure it is in good condition and inserts into the plug ends. Never repair cracks, breaks, cuts, or tears with tape. Either discard the extension cord or shorten it by installing a new plug end. Take care not to run extension cords through doors or windows, where they can become pinched or cut. Use only grounded equipment and tools, and never remove the grounding pin from the plug ends. Do not hook multiple extension cords together to reach your work; just get the right length of cord for the job.

Other things to check are hanging pendants and electrical outlet boxes, which are becoming widespread due to their use in keeping cords off floors and out of the way. In a recently visited facility, there was an accident from an unguarded hanging outlet shorting out when it was “caught” by a forklift passing under it. Fortunately, the forklift driver was not electrocuted. Check electrical pendants for proper strain relief, type of box, and guarding, if needed. Finally, check the electrical panel. Ensure a three-foot clear space is kept in front of it at all times. Also, clearly label each circuit breaker.

Can you hear me now?

Many areas within research facilities are inherently noisy. Excessive noise can result from equipment in use, such as sonicators, high-pressure air cleaning equipment, and wet-vacuum systems.

A quick and useful method for checking areas for excessive noise is the “conversation test.” Standing one to three feet away, attempt a normal conversation with another person in the noisy area. If conversation is difficult or impossible, then the noise might be excessive. Since exposure to loud noise can result in loss of hearing, OSHA limits employees’ noise exposure to 90 dB averaged over an eight-hour work shift.2 Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is permanent and cannot be treated medically. This type of hearing loss is usually noticed by a reduced response to frequencies above 2,000 Hz. As normal human speech is in the 2,000 to 4,000 Hz range, NIHL is debilitating at work and in daily life.

If noise levels exceed 85 dB, the employer must implement a hearing conservation program (HCP) for exposed employees. The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists recommends a more conservative threshold of 85 dB as an eight-hour time-weighted average.3 Monitoring, annual audiometric testing, hearing protection, training, and record keeping are required under the HCP. Have noisy areas evaluated by a qualified person knowledgeable in occupational noise, measuring techniques, data analysis, and control alternatives.

Until next issue, remember: SAFETY FIRST!

References:

1. Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, Lighting Handbook, 10th ed., New York, 2010, http://www.iesna.org/.

2. US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, “Occupational Noise Exposure,” 29 CFR 1910.95, Washington, DC, 2008, http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=standards&p_id=9735.

3. American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, Threshold Limit Values and Biological Exposure Indices, Cincinnati, 2011, http://www.acgih.org/.